Introduction: The City Within

Most of us remember the cell from high school biology: a simple, jelly-filled blob with a nucleus in the middle. It’s an easy image to recall, but it’s profoundly misleading. This simplified model is like describing New York City as just a big building on an island. The reality is infinitely more complex and fascinating.

Your cells are not simple blobs; they are bustling, microscopic metropolises. Each one contains intricate systems that function like a city’s infrastructure. There are power plants generating energy, factories synthesizing materials, a sophisticated shipping network delivering packages, and a ruthlessly efficient waste management system. Everything operates with a level of precision and coordination that is difficult to comprehend.

Forget the simple diagram. In this article, we will pull back the curtain on this inner world and reveal five of the most surprising and impactful secrets your cells have been keeping. Prepare to see the fundamental units of your own body in a completely new light.

Your Cells Are Powered by Ancient Invaders

- Your Power Plants Are Ancient Bacterial Squatters

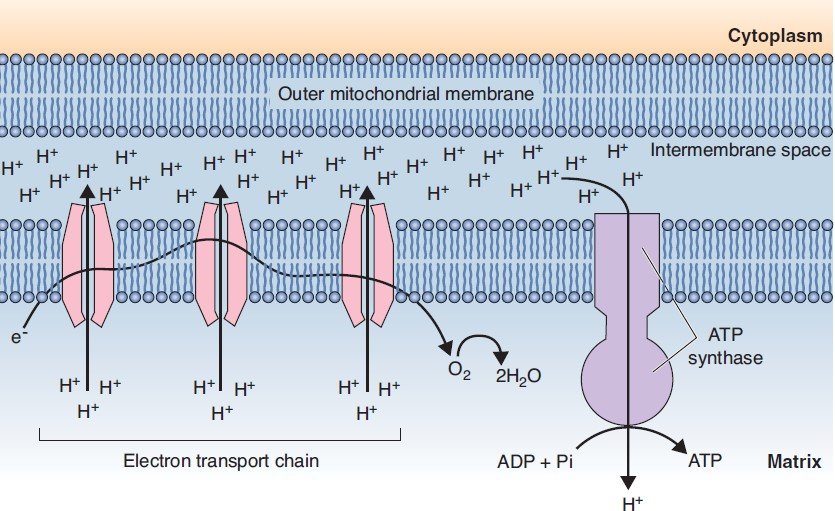

Every cell has its “powerhouse,” the mitochondrion, which is responsible for synthesizing ATP, the primary energy currency of life. But the origin of this critical organelle is one of the most astonishing stories in biology. The leading theory suggests that mitochondria didn’t evolve with our cells from the beginning; they were once separate, independent life forms.

According to this theory, ancient anaerobic eukaryotic cells once “endocytosed,” or swallowed, aerobic microorganisms. Instead of being digested, these microbes formed a symbiotic relationship, becoming intracellular parasites that eventually evolved into the mitochondria we have today. Structurally, each mitochondrion still reflects this history, possessing a smooth outer membrane and a highly folded inner membrane whose folds are called cristae, which enclose a central space called the matrix.

It’s a profound concept: a core component of our own cellular machinery, the very engine that powers our existence, was likely once a foreign invader that took up permanent residence.

An Ultra-Precise Postal Service Runs Your Inner World

- A Microscopic Postal Service Delivers Cellular Packages with Frightening Precision

A cell is a whirlwind of activity, constantly producing proteins and other molecules that need to be delivered to specific locations. To manage this, the cell employs a logistics network of stunning sophistication. The shipping containers of this system are “coated vesicles,” tiny membrane-bound sacs (like COP-I, COP-II, and clathrin-coated vesicles) that package the molecular cargo.

But how does a package know where to go? The secret lies in a molecular “zip code” system using proteins called SNAREs. Each vesicle has a specific v-SNARE on its surface, and each target destination (like another organelle or the plasma membrane) has a complementary t-SNARE. A vesicle will only dock and fuse with its target when its v-SNARE correctly binds to the corresponding t-SNARE. This interaction is incredibly specific, like a unique key fitting into its one and only lock, ensuring every delivery is made to the correct address.

The critical importance of this system is perfectly illustrated by how Botox works. The botulinum neurotoxin functions by cleaving a specific t-SNARE protein (SNAP-25) at nerve terminals. This prevents synaptic vesicles from docking and releasing their neurotransmitter cargo. Without the delivery of this chemical signal, the muscle cannot contract, resulting in paralysis.

Cells Routinely Eat Themselves to Survive

- To Stay Healthy, Your Cells Must Eat Themselves

The idea of a cell eating itself sounds like a destructive, suicidal act. In reality, it’s a fundamental process for survival and renewal known as “autophagy,” which is the digestion of a cell’s own components. This isn’t a sign of malfunction; it’s a vital housekeeping function.

The process begins when membranes derived from the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) envelop an old or damaged organelle, like a worn-out mitochondrion. This encloses the component in a double-membraned sac called an “autophagic vacuole.”

This vacuole then acts like a trash bag, moving through the cell until it fuses with a lysosome—an organelle filled with powerful digestive enzymes. The resulting structure, an “autophagolysosome,” breaks down the contents into reusable molecules that the cell can recycle. This act of self-cannibalism is how cells remove debris, clear out damaged parts, and renew themselves from within.

Unwanted Proteins Are Tagged for Destruction

- There’s a Molecular ‘Kiss of Death’ That Marks Proteins for Destruction

While autophagy handles large-scale cleanup of organelles, the cell has another, more targeted system for dealing with smaller threats like unwanted or damaged proteins floating in the cytosol. This quality-control mechanism relies on a molecular executioner called the “proteosome,” a cylindrical complex of proteases that acts like a microscopic paper shredder.

This disposal system isn’t random. Unwanted cytosolic proteins are specifically “marked for destruction” through an enzymatic process that tags them with a small protein called ubiquitin. This ubiquitin tag is the molecular equivalent of a black mark, a signal that cannot be ignored.

Once a protein is tagged, it is delivered to the proteosome. The proteosome recognizes the ubiquitin signal, unfolds the doomed protein, and feeds it into its central chamber, where it is broken down into small peptides. It is a highly efficient and targeted system for eliminating specific proteins that could otherwise cause harm.

Your Cell’s Skeleton Can Help Diagnose Cancer

- Your Cell’s Internal Skeleton Is a Key Tool in Cancer Diagnosis

When we think of a skeleton, we imagine a static, rigid frame. The cell’s internal “cytoskeleton,” however, is a dynamic and adaptable network of filaments, including microtubules, actin filaments, and intermediate filaments. This framework is responsible for maintaining cell shape and serves as a highway system for intracellular transport. But one class of these filaments has a surprisingly powerful clinical application.

The key lies with intermediate filaments. Unlike other cytoskeletal components, different types of cells produce different types of intermediate filament proteins. For example, epithelial cells make keratin, while certain glial cells in the nervous system make Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP).

This cellular specificity is invaluable for tracking down the origin of a cancer that has spread. Imagine doctors find a metastatic tumor in a patient’s liver. By testing its cells, they discover the cells are full of keratin filaments. Since liver cells don’t make keratin, this instantly tells them it’s not liver cancer. Instead, it is a carcinoma—a cancer that originated in epithelial tissue, such as the lung, colon, or breast—that has spread to the liver. This molecular detective work is critical for choosing the correct treatment.

Conclusion: The Universe Within

The simple drawing of a cell from our school days is a shadow of the truth. Within each of us are trillions of microscopic cities operating with ancient symbiotic relationships, ruthless efficiency, and a precision that rivals any human-made machine. From repurposed bacteria powering our every move to molecular zip codes ensuring flawless deliveries, the cell is a universe of complexity and wonder.

As we continue to peer deeper into this inner world, we are constantly uncovering new layers of sophistication. It leaves us with a humbling thought: given the incredible complexity we can already see, what other secrets might our cells still be keeping?